On Patrol With Munich's Bounty Hunters

This article originally appeared in the Munich Found

The team of plainclothes agents moves in, and takes position. The suspect is in the corner, the gentleman with the pierced face, shaved head, tattoos and a scuffed leather jacket. He is almost 2 meters tall.

I’ve seen this kind of thing before, riding shotgun with cops in New York and St Petersburg, but Munich’s kopfgeldjaeger, “head-hunters”, are different. They’re despised and mocked: I met one who’d appeared on a TV talk show as having one of the, “worst jobs in Munich”.

But the MVV Transit Ticket Controllers I met are, for all the world, a bunch of pussycats.

“It’s a game,” says Wolfy, amiable team leader of this 8-person crew which prowls the city’s public transport system in search of scofflaws. “They see us coming, and we see them see us coming.”

It certainly appears that way during the afternoon I spent sniffing out crime with them aboard Munich’s subways and trams. The affability of this group was was something of a let-down. I’d somehow expected (as had my editor, who also had hoped for tales of terror from below) that these folks would would be a right hard bunch.

Maybe they’re friendly because they’re hardly necessary: of almost 300 million riders last year on the Munich underground, only a paltry 3% to 5% actually ride “black”, or without a validated ticket. Those who do risk a fine of DM60 - money the MVV, Munich’s Mass Transit System, says you’d be better off spending on beer.

There’s really no “black riding” culture here as exists other cities like Amsterdam, where rider’s groups defy the law en masse. In Munich, most cough up. So relaxed was the control team I rode with that they told me I could say anything I wanted to about their methods, patrol tactics and procedures.

The Basics

Your chances of getting caught, and the patrol schedule, change like the wind. But one static figure is that there are 22 teams of eight agents on staff at the MVV. They’re not cops - indeed their powers of arrest are identical to yours as a citizen.

But they have the power to inspect your ticket, and issue fines. They can hold you until police arrive if you’re recalcitrant or they don’t believe you’ll pay (thoughfully, though, if you live in Germany, a bill will arrive at your house).

The Day

I met the team at the Hauptbahnhof, the central railway station, under which their headquarters is located behind one of those mammoth steel doors you pass daily and never notice. As we boarded the U4 Wolfi and I chatted about statistics and the risks.

“Most people are polite,” he said. “It’s not really a dangerous job. And people know who we are - you see five or eight people standing clustered on the platform talking, and carrying no bags, you figure they’re us - and you’re right.” Sometimes teams lurk at the top of the stairs to the subway, doing “border checks” to nab passengers alighting from the U-Bahn. One thing these folks have done is heard it all.

There’s little you can say to them that’s not been tried before, probably tried in the last hour. For the record, the most commonly used excuse is, “The machine was out of order,” followed closely by “I lost my ticket”, both of which go over about as effectively as the old yarn involving your homework and your dog.

These are, however, reasonable folks. “We understand that this is a difficult system for foreigners to grasp,” says Gaby, a 20-year veteran and another huggably amiable - when she’s not asking for your ticket - agent. “If people don’t understand and we believe they tried to, we’ll give them a break.”

But mess with them and you’re in for it. “If we don’t believe you,” says Wolfi, “we’ll fine you, and if we think you won’t pay we’ll hold you for the police. A mistake is a mistake, but ‘paying’ is international.” And don’t try the old “I-don’t-speak-German” dodge - all teams have an English speaker and many a French speaker, and all are armed with Wolfi’s custom-made chart which gives you the bad news in languages from Czech to Spanish, and Italian to Serbo-Croat.

We board another train, and the doors close. Instantly all scatter, whipping out their ID cards like Kojak at a raid, their presence going over like, well, Kojak at a raid. The skinhead I discussed earlier bristled, and I thought we were in for some action. “You got me,” he says, smiling.

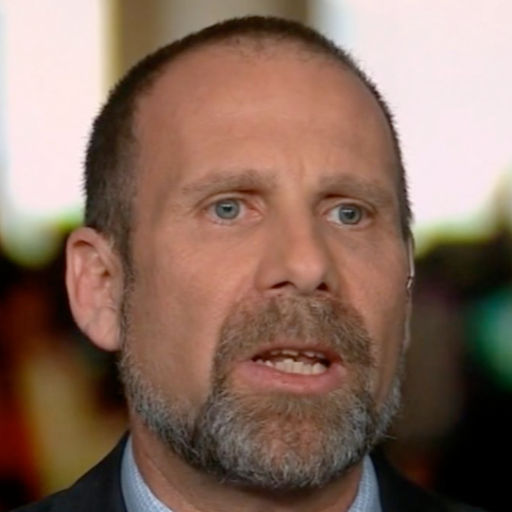

Willi, the rookie of the group with just a year on the job (and the subject of that episode of the Sabrina show) tickets the perp, who politely hands over all documents requested and signs on the dotted line.

When it was over, the skinhead says something which convinces me the rest of my day is to be rather dull.

He says, “Thank you.”

Desperate for some action, I tried one last question: “Do people ever run?” “Sometimes,” said Wolfi. Ah ha! “So, do you give chase?” I asked, breathlessly.

“No.”