A Soviet Spoke in the Wheels of Progress

Note: this article was written while I was researching the Lonely Planet Russia, Ukraine & Belarus guide in 1994, and every time I crossed the border I became more fascinated by the operation and the team that was changing out the wheels. So, one miserable and cold day, I took the train from Warsaw out to Kuźnica and spoke with the teams changing the wheels. A version of this article made it in to the LP Guide in 1995. I’ve updated it a bit, changed it to past-tense, and fixed some spellings and stupid errors I made at the time - Nick

Life has changed very little over the past few years for Stanislaw Kudrzycki, a shift supervisor for the Polish national railway (PKP) and his 19-person crew at Kuźnica on what is now (1994) the Poland-Belarus border. At the railway station of this desolate town, a 24-hour a day operation functioned in exactly the same way it did when it was established in 1972 to process passenger trains crossing into and out of the Soviet Union.

A legacy of Tsarist xenophobia is that Russian rail gauge is 85mm wider than European gauge; the reasoning was that foreigners intending to invade by train would first need to capture rolling stock.

If the system ever did thwart foreign invaders (it managed to severely impede progress of Nazi troops, who scrambled to regauge the lines to Moscow during World War II) it caused far greater frustration to rail travelers from Europe, who were compelled to change trains at the Polish - Soviet border.

A Bit of History

As the Soviet authorities began to rely upon tourism as an important source of hard currency income, they were forced to change the abominable border conditions that had required passengers to take all their belongings and walk up to 500m to board a Soviet train.

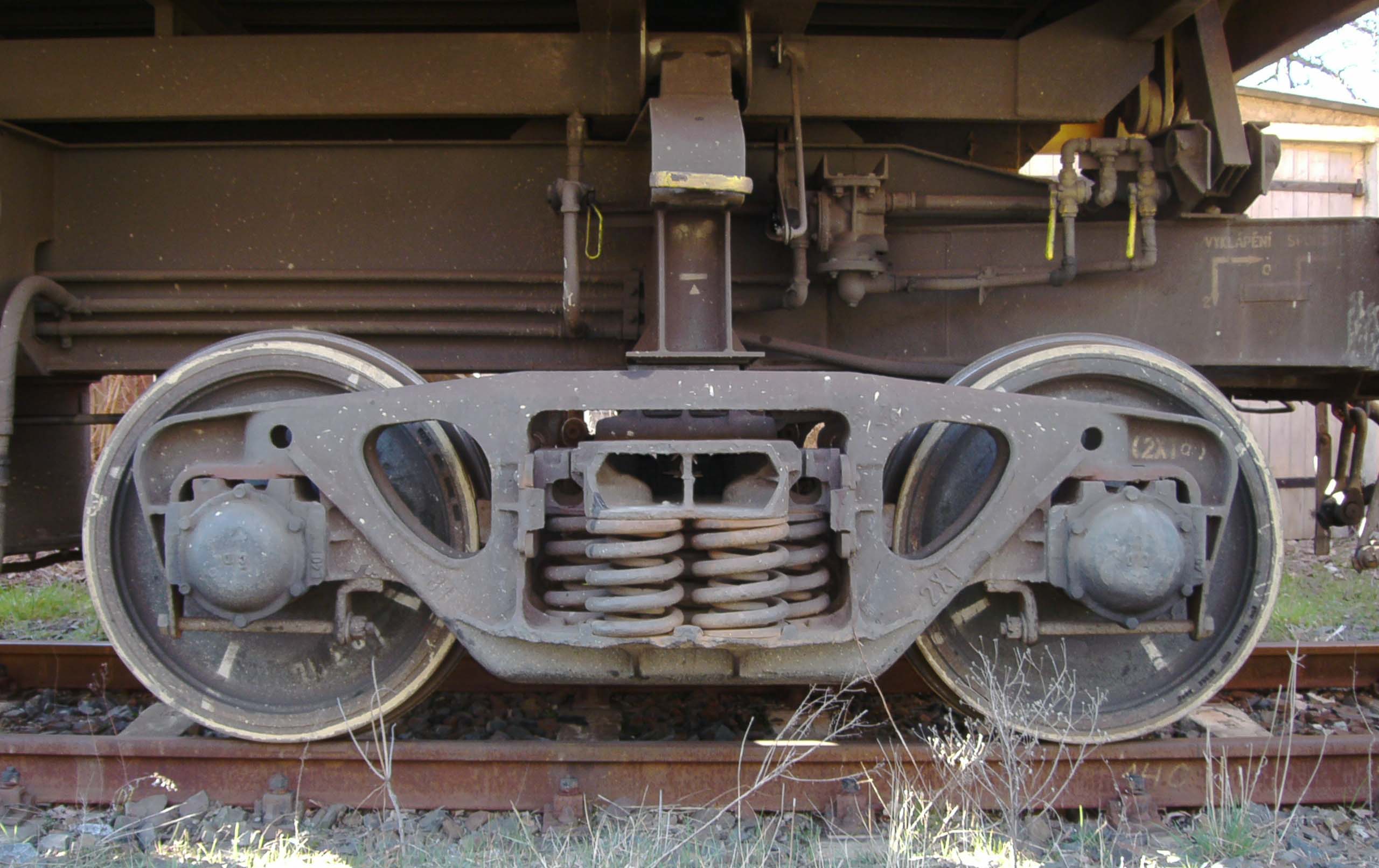

In the 1960s, they redesigned their train cars to the little more than flat bottomed cargo containers with seats, which could be placed upon changeable wheel truck assemblies, or bogie.

Train Bogie, photo by Ketamin (click to see on Wikimedia)

The bogies comprised two axles, four wheels, shock absorbers and a seat upon which the train can be fastened using a “male/female” connector in the manner similar to a key fitting into a lock. For trains from Europe, the European-gauge bogies were removed and rolled out from underneath the cars, and then Soviet-gauge bogies rolled in and attached. The outbound procedure is the reverse.

In 1972 the Soviets constructed a bogie-changing station at Kuźnica and contracted PKP (Polskie Koleje Państwowe, the Polish State Railroad) to operate and maintain it. Despite the facility’s decidedly Soviet appearance, it was always a Polish-run operation.

As a train reached the border, its cars were separated and placed next to hydraulic lift platforms - which work in essentially the same manner as giant car jacks. The cars were then hoisted 2m off the ground, its bogies rolled out from beneath the train, and new bogies rolled in. Once the new bogies were manually lined up with the lynch point, the wagons were lowered onto the new bogies, fastened, and then re-connected with one another.

Dangers at Every Turn

It was a complicated, labor intensive operation. After each car was lifted, workers walked underneath and attached the bogies to a steel cable which pulled them down the track and off to a siding where they were stored until the train’s return. When the correct bogies for the direction of travel were rolled in, they were manually positioned (often using crude tools, like bent pieces of track as makeshift hammers, and extra long crow bars to rock the bogies backwards and forwards until the connecting points were aligned.

To those unaware of what was happening (and this included most visiting Westerners), the procedure could be a harrowing experience with threatening Cold War overtones. Passengers were forbidden to leave the cars during the operation, which often took place very early in the morning. Passengers spent the turnaround time watching workers scurrying beneath their windows, while armed Polish soldiers patrolled the kilmometre-long stretch of the work area. The eerie silence was broken only by the constant slamming of bogies being rolled into a line and down the tracks.

Every aspect of the procedure, which took between 60 and 90 minutes per train, was dangerous. In winter, when the average temperature routinely fell to minus 15 degrees Celsius, workers stood for periods of up to two hours out in the cold, before retreating to an overheated lounge area; illnesses were common.

The hydraulic lifts, which were both electrically and manually operated during the procedure, failed on at least one occasion, sending one of the 50 ton cars and its passengers crashing to the ground.

Workers spoke of one woman passenger being killed, and seven people losing limbs, when they were caught between 9-ton bogies being rolled down the track. Drunken passengers routinely fall out of the cars.

And there’s always the danger that a conductor will forget to lock the door to prevent entry to a car’s toilet, which empty directly onto the tracks. Should someone flush during the wheel changing procedure, the consequences would have been unfortunate for any worker who happened to be standing on the tracks beneath the drain output.

Kuźnica, five hours east of Warsaw, is a tiny farming town. In the 1990s, its rail crossings saw massive business as Russians and citizens of other former Soviet republics came by rail lugging all their worldly possessions to sell in Warsaw’s markets; they would wait in line at the border for an average of three days to cross into Poland.

On their return, having sold their possessions, they’d buy a train ticket from Warsaw to Kuźnica, where they’d cross the border by foot, walk a few kilometres to the Grodno station, and then pay in roubles for onward transportation.

Where Mr. Kudrzycki and his crew used to be controlled absolutely by the military – even to the extent that they had to request permission to go to the toilet – the fall of the Soviet Union left them very much under their own control. In the 1990s, the crew made it very clear to the Russian border guards that they were merely being tolerated .

Even the once powerful and feared Russian train conductors - who would use any opportunity to exercise their authority - tood sheepishly by as the workers went about their business. “They still try to throw their weight around from time to time,” said Mr. Kudrzycki, “but now, they’re just a joke.'

“We used to do our job while the army stood guard, keeping passengers in the cars, making sure people weren’t taking photographs of the facility or sniffing around near the border,” one of the workers said. “Now the Army is ‘protecting' us from the Russians, trying to keep them out!” The whole crew, having a tea break between train arrivals in their smoke filled lounge, laughed, and the crew’s tea-break ended as the St. Petersburg-Warsaw train was pulling in.

Mr. Kudrzycki made his way to to the 15m-high control tower. Standing at his control console, he pressed one of several dozen lighted buttons as he spoke, but the action had no discernible effect. A worker’s voice blared over a two-way radio speaker: the remote control is not functioning, so he would need to complete the tasks manually.

“That’s normal,” Mr. Kudrzycki said, pointing scornfully to the console, which looked like a 1950s comic strip version of a “control panel of the future.”

“I’ve been here for four years, everyone else since 1972, and they only installed a radio last month. Before that we would use hand signals, or send messages in a chain: he tells him, that guy tells the other guy, the other guy comes upstairs and tells me …'

There may be a lot of problems, but Mr. Kudrzycki was still sure of at least one thing: he’s wasn’t in danger of being laid off. “In Portugal,” he said almost wistfully, “they have the wide gauge rails as well. But they’re using a new technology. They have contractible axles on the trains; as they cross the border the axles expand by springs and become wide enough to run on the rails.'

“But,” he continued, “my job’s safe. Do you have any idea how expensive that system is?”

Note: Wikipedia lists the following:

The Cross border BG freight line and facilities in Poland are being upgraded from 2020 as previously it was believed traffic was re-gauged at Kuźnica Białostocka or transferred between wagons at Sokółka…PKP PR Kuźnica Białostocka <> Hrodna local trains were discontinued at the December 2015 timetable change as they were to be replaced by PKP IC services between Warszawa and Hrodna. Owing to funding issues these did not commence until 4 September 2016 with a Kraków <> Hrodna portion of the Krakow <> Suwalki train. PKP work these to Hrodna, with it is believed BČ diesels working all BG freight. Passenger services were suspended due to the pandemic and have not resumed, and there are no plans to do so for 2022/23.