The Gen Z blacksmith breathing new life into an ancient art

This article, by Patrick Greco originally appeared in the Albany Times Union. It is reproduced here under license with the Albany Times Union. Photographer Patrick Grego, provided courtesy the Times Union in Albany, N.Y.

For more information, please visit Rocky Hill Forge’s Instagram.

In Columbia County, Spijk Selby is forging the future of traditional blacksmithing

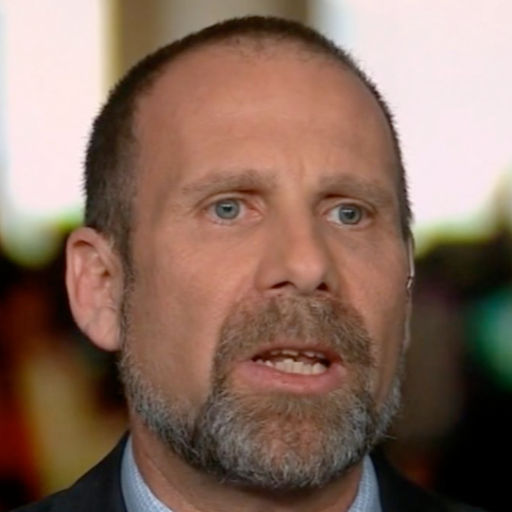

Spijk Selby hammering out a knife blank at his Ghent, NY forge - Patrick Greco, Albany Times Union (Click image to enbiggen)

GHENT — Every morning Spijk Selby wakes up and walks a short distance from his family home in the forested hills of Columbia County to a decagonal structure tucked into the trees. There, between sips of coffee, he lights a coal fire that at its core reaches temperatures exceeding 3,000 degrees.

“This fire is at the heart of everything I do,” said Selby, 23, a blacksmith and traditional maker. His hands, trousers and button-up shirt are all blackened by coal. “Once it’s lit, I heat up steel and bang on everything that doesn’t look like a knife, until it looks like a knife.”

A blacksmith was once fundamental to the everyday functioning of any town. They made tools, knives and household necessities. But today, in the age of automation, there are only an estimated 5,000 to 10,000 blacksmiths practicing the craft in the United States. Of that number, only an estimated 10 percent do it professionally.

With a coal-burning forge, a large iron anvil, and a hammer in hand, Selby practices traditional blacksmithing methods — much as they’ve been practiced for thousands of years — to make knives, daggers, copper dishes, and silver jewelry, though his primary focus is culinary knives.

Unlike contemporary methods designed for mass production and speed, traditional blacksmithing and knifemaking demand much more time. A single knife can take up to 30 hours to complete.

“When I make a knife, all my attention is on that one knife for hours and hours,” Selby said. “I’ve obsessed over every part of it, and I’ll notice details that somebody making 500 at a time simply cannot.”

Selby works out of a newly completed workshop named for the rocky hill it sits on: Rocky Hill Forge. That is where the young blacksmith is keeping centuries-old methods of blacksmithing and woodworking alive in the Hudson Valley.

“If people don’t keep practicing these methods, they will die, and they won’t come back,” he said.

Sparking Interest

Rocky Hill Forge is the manifestation of Selby’s lifelong interest in all things medieval. Originally from Munich, a city rich with medieval history and art, Selby moved to the Hudson Valley with his family when he was 4 years old.

“Knives and swords and making them always really appealed to me,” he said.

His interest in blacksmithing was sparked when at the age of 9, he saw a blacksmith making nails at a crafts fair. “I stood there for a while and was just obsessed with it,” he remembered. The blacksmith offered to let the young Selby strike the iron, and he’s been doing it ever since.

As a teenager, he studied at Prospect Hill Forge, an educational forge in Waltham, Mass. There, he learned the basics of blacksmithing with Carl West and Michael Bergman. The commute was far from the Hudson Valley so he found a blacksmith named Noah Khoury through Creative Art Time Studios in Delmar.

Then, in the spring of 2013, Selby met Chuck Wales, a blacksmith in the Berkshires who ran the forge at Hancock Shaker Village. He began an apprenticeship, spending his entire summer practicing traditional blacksmithing over a hot forge until eventually he ran the forge himself.

A Forge Of One’s Own

After graduating high school at The Albany Academies in 2015, Selby, like most graduates, was figuring out what he wanted to do with his life. He knew he loved blacksmithing, but he needed a shop.

Working outside in his parents’ backyard with a makeshift forge, he dreamed of a professional workshop that would both demand respect and convey that he was serious about becoming a full-time blacksmith.

That dream was set in motion when he received his first big contract — a company based in California ordered 40 of his handmade knives. How much does an order like that pay? “It’s significant,” Selby said. “Enough to build a shop.”

After completing the order, it took Selby 2 ½ years, including a year of research, to build Rocky Hill Forge from the ground up.

With a copy of Toby Wrench’s “Building a Low-Impact Roundhouse,” Selby built his workshop using traditional methods by himself. The entire decagonal structure is self-supporting. It has a stacked reciprocating roof. The floor is timber framing made from nearby fallen trees. There’s no foundation. All the joists for the floor form a webwork that supports everything.

“I set out to build this shop on my own, and that’s exactly what I did. This was not a good nor sane decision,” he joked.

With his workshop complete, Selby is now able to work full-time as a blacksmith. His last finished knife sold for $450.

“It takes considerably more time to make a knife with this method, but what you get is something really special,” he said.

Staying Sharp

On weekends, Selby can be found sharpening knives at community events, food co-ops, and farmers markets across the Hudson Valley and Western Massachusetts.

“I notice that a lot of people feel the same way — dull knives aren’t nice to use, and they’ll pay you to sharpen them,” he said.

His knife-sharpening events have been popular in towns such as Woodstock, Catskill, Great Barrington, Chatham, and Hudson.

“This is the second season Rocky Hill Forge has attended the Hudson Farmers’ Market,” said Monica Jerminario, 38, administrator of the Hudson Farmers’ Market. “Spijk is honest and pleasant. The in-person on-site sharpening that he provides shows the true artistry of whetstone sharpening while entertaining our customers.”

Currently, Selby sharpens around 2,000 knives a year. Of course, he uses traditional methods to do so.

“It’s another rabbit hole that I’ve gone down,” he said.

Forging the future by preserving the past

Like most artists, Selby thinks about the lasting impact of the objects he makes. And working a millennia-old profession with hard enduring metals like iron and silver, he often contemplates his own mortality.

“It’s a mystic craft. I’m thinking about how my great-grandkids are going to feel about this knife — will it sit in a drawer and rust, or will it be something they actually prize, use and love?” he said.

One of the final steps in creating a knife is marking it with a touch stamp. It’s the blacksmith’s signature, tying their name and reputation to each work for as long as that creation exists. Selby, highly aware of his own impermanence, marks his creations with a small tree.

“Marks that are left by this tool are certainly going to outlast me,” he said. “I don’t want my reputation to be awful after I’m dead. Everything I do needs to not only hold up now but for as long as humanly possible.”

In a time when changing career paths is common among young people, Selby doesn’t have a backup plan.

“If I did anything else, it would take my attention away from blacksmithing,” he said. “It needs all of my attention.”

Patrick Grego is an award-winning writer based in the Hudson Valley. He believes in the power of storytelling to bring people together.