Divert to Where? Quality Policing Podcast

This is a transcript of a 30-minute podcast that ran at Quality Policing. It was written and produced by Nick Selby. NB: Floyd, the man described in this story, gave his explicit, written permission to use his name and likeness for the podcast and the accompanying article in the Dallas Morning News.

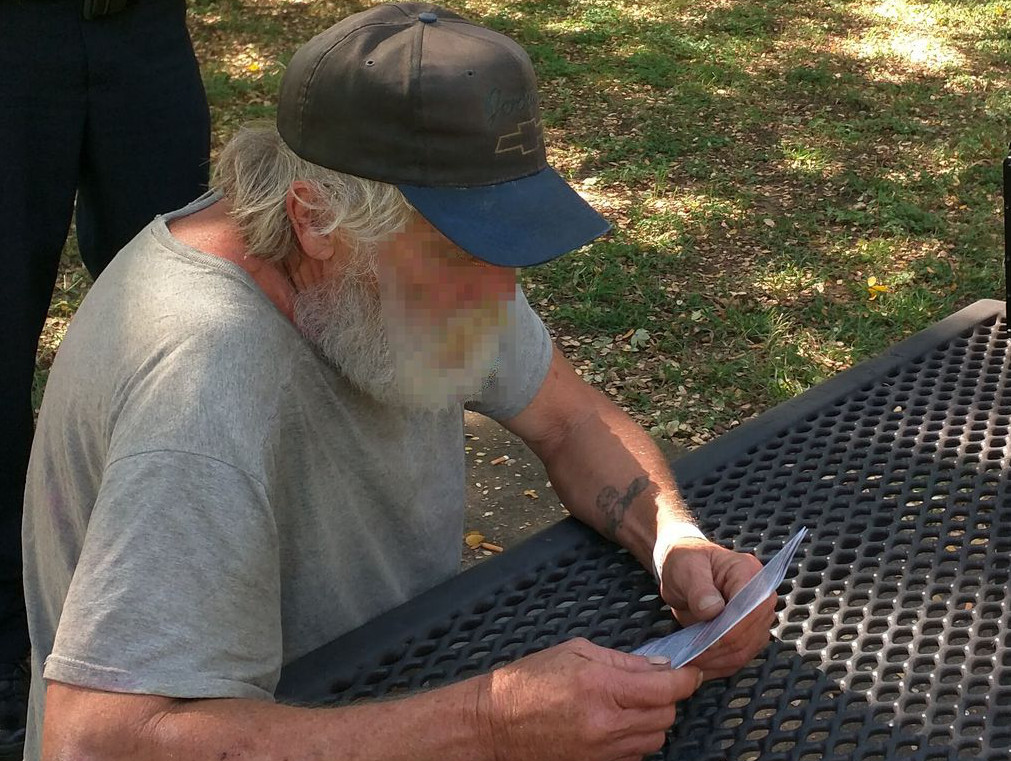

NARRATOR (Nick Selby): About one in four people arrested in America suffer from both severe mental illness and drug or alcohol abuse. The bigger problem might well be the people with mental illness who aren’t arrested. People like Floyd, a clinically depressed 64 year old homeless man with broken ribs, sleeping on the bench of a picnic table in a Texas park.

FIELD RECORDING

FLOYD: I even thought about killin' myself.

KEN BENNETT: You been thinkin' about killing yourself?

FLOYD: Yeah.

KEN BENNETT: Have you had those thoughts today?

FLOYD: Yeah.

KEN BENNETT: How would you do it?

NARRATOR: That’s Ken Bennett, the mental health coordinator for the police departments in the sister cities of Hurst, Euless and Bedford, Texas. They’ve been talking with Floyd for less than five minutes, and they’re asking how he wants to kill himself. Tell a cop you’re suicidal, and they need to determine whether you have a plan … if you’ve really thought about it.

Floyd

FIELD RECORDING

FLOYD: I thought about hangin' myself.

KEN BENNETT: Thought about hanging yourself today, Floyd?

FLOYD: Yeah.

KEN BENNETT: Just kind of tired of it.

FLOYD: Yeah. I’m sick of it.

Okay. All right. We can get you some help that way.

NARRATOR: This is the kind of thing that people say they want police to do. All too often we don’t. We can’t. Most agencies don’t have a culture that supports this kind of thing.

COLT REMINGTON: At one point during the during the incident, the confrontation, he even brought the gun down from his head and wrapped around into the chamber right in front of us.

NARRATOR: That’s my friend Colt, who resigned as a mental health peace officer this month.

COLT REMINGTON: My name is Colt Remington and I’m a former police officer in the Dallas Fort Worth area.

NARRATOR: Yeah, his name really is Colt Remington. Colt is a former Marine sergeant who served in Iraq and Afghanistan. And he’s telling me about one of the times he convinced a suicidal man with a gun to his head to put the gun down and come get some help.

Colt Remington

NARRATOR: That’s Colt being modest. The ‘somehow’ was that Colt talked to him for about 15 minutes, despite the gun being loaded, cocked and so close to him. And the man finally agreed to get help. Afterwards, supervisors who watched the video told Colt that he should have shot the guy, that it was dangerous, that he hadn’t shot the guy.

COLT REMINGTON: But the craziest part about that is rather than coming up and being like, ‘Hey, great job for not killing a guy,’ it was, ‘Why didn’t you shoot him?’ You know, ‘you should have shot this guy.’ That’s insane.

NARRATOR: The thing is, the way mental health care in America works right now, both of them are right. The supervisor was right. Just because somebody’s mentally ill doesn’t mean they’re not going to kill you. The man threatening suicide was a criminal and he had stolen the gun. And Colt was right. Usually, Graham versus Connor - the Supreme Court ruling applied to cops who used deadly force - is something we hear about when the cop pulled the trigger.

The ruling says that the reasonableness of a particular use of force must be judged from the perspective of a reasonable officer on the scene rather than with the 2020 vision of hindsight.

But here’s a case in which we have Colt, the officer, saying that to him, with his battlefield and gunfight experience, he didn’t feel his life was in danger. He didn’t need to shoot. Someone else can’t just look at the video and say Colt should have shot the guy because that’s exactly the kind of Monday morning quarterbacking the rule bars.

This is one of the biggest challenges in America. Most departments are training like Colt’s old agency – in a reactive manner.

More progressive agencies are now using something called the Memphis Model, or Crisis Intervention Training, through state mandated courses for police officers. I’ve taken about 24 hours of CIT training, and it’s dramatically better than nothing. I’m sure it saves lives, but the thing I keep thinking about is that for the training to be helpful, you need a crisis.

. . .

If you’re like me, you grew up thinking that America was a great, somewhat flawed but fundamentally fair country. I always believed that if you’re truly mentally ill, you’ll be cared for in a community mental health center or a county or state hospital. I’m old enough to not only remember, but to have gone to the Soviet Union, where the mentally ill were imprisoned. We’re not like that, right?

SHERIFF BILL WAYBOURN: Our jail population this morning was 4,108, and 25% of those people are mental health patients of some sort. They’re verifiable on mental health meds. They are being counseled and dealt with as if they … well, they are mental health issues.

NARRATOR: Meet my old boss.

SHERIFF BILL WAYBOURN: I’m Sheriff Bill Waybourn of Tarrant County, Texas.

NARRATOR: Tarrant County is Fort Worth and the cities to the east and west of it, which are home to about two million people. So he’s saying that, this morning, more than a thousand people in the county jail in Fort Worth are mentally ill jail inmates. That’s about average.

Yeah, this is the kind of problem whose scale just sneaks up on most people.

There are ten times more mentall ill people in America’s prisons and jails than in state mental hospitals. Some of our nation’s biggest psychiatric inpatient clinics are in county jails in Chicago, Los Angeles, and New York. I guess this shouldn’t shock people, but I know it does because they tell me it does. Part of this is probably because we in law enforcement are incredibly bad at communicating important trends like this.

Don’t get me wrong, cops will gripe, but it’s not in our nature to complain about the mission. And mental health has become a big part of the mission. And it’s not like we didn’t say anything at all. If you remember the attack on Dallas police officers in July of 2016, you probably remember the words of then Dallas Police Chief David Brown.

ARCHIVAL AUDIO

CHIEF DAVID BROWN: We’re asking cops to do too much in this country, not enough mental health funding? Let the cop handle it. Not enough drug addiction funding? Let’s give it to the cops.

NARRATOR: On the other hand, we have activists and citizens rightfully demanding to know how things can go so wrong between cops and the mentally ill. In Oklahoma City this September, officers fatally shot a man who was deaf and mentally ill after he refused to drop a two foot pipe and get on the ground. How could that have happened? What about de-escalation training? Where’s the mental health awareness training? What are those terms even mean? Like many things at the intersection of law enforcement, citizens and the news, mental health policing is complicated.

So let’s untangle it. Starting with why police and the mentally ill intersect so often. And then we’ll hit the streets with officers and the behavioral intervention unit. What just might be America’s most progressive, proactive mental health unit.

What I’m about to say really seems to surprise a lot of people. Today’s mental health situation in America is the result of cuts by Republican and Democratic administrations over the past 50 years. No party, no politician, no individual policy is to blame. It’s a bipartisan mess of good intentions and terrible planning of lofty ideals, meeting government, budgetary reality.

And it all starts with chlorpromazine.

Back in the 1950s, when the average stay in a mental asylum was about 11 years, a common treatment was an orbital lobotomy in which surgeons would cut the connection from the brain to the prefrontal cortex.

KEN BENNETT: And you got to remember, this was going on even in the ’60s all the way up until the 70s. So this wasn’t something that was that happened, you know, 80 or 90 years ago. I mean, this is a very recent thing that we were doing.

NARRATOR: That’s Ken Bennett again.

KEN BENNETT: But in 1955, they came out with a drug called Thorazine, and they thought this drug, Thorazine, was going to be the cure all.

NARRATOR: Thorazine is the best known brand name for chlorpromazine. What it promised was something like a chemical lobotomy. Patients who had been impossible to handle could finally be de-institutionalized. As long as they took their meds, they could be sent back home. It was a miracle and we needed one.

ARCHIVAL AUDIO

PRESIDENT JOHN F KENNEDY: Almost every American family at some stage will experience or has experienced a case of mental affliction. And we have to offer something more than crowded custodial care in our state institutions. Our task is to treat them more effectively and sympathetically in the patient’s own community.

NARRATOR: The Kennedy administration began the push to get mental patients out of the asylums and drive them toward local and community clinics, which the president said would be more effective and humane. The Community Mental Health Act signed the month before his assassination, was to provide funding to states to build 1500 community health centers. But the launch of Medicaid in 1965 created a perverse effect. It wanted to bolster the incentive to states to get people into those local community clinics that would receive federal funding. But that funding never fully materialized, and it has been cut and cut ever since. Medicaid, which was to be the health care safety net for indigent and poor Americans, just never wanted to cover mental health costs. But state budgets then, as now, presume that Medicaid does.

In 1980, the Carter administration passed the Mental Health Systems Act, which sought to expand community mental health centers remit to handle substance abuse disorders. But Carter lost his re-election bid for the second time in 17 years. A president signed broad legislation to introduce change to American mental health treatment, but he couldn’t follow through. Reagan era austerity and tax cut policies led Congress to cut federal mental health funding significantly, and as asylum conditions worsened, suits to protect the rights of the mentally ill resulted in rulings across the country against involuntary commitment without a specific and articulable danger to the patient or others. The budget cuts opened the floodgates, sending millions in an exodus from mental hospitals to streets and parks, and the contemporary homelessness problem was upon us.

ARCHIVAL AUDIO

PRESIDENT BARACK H OBAMA: For years now, our mental health system has struggled to serve people who depend on it. That’s why under the Affordable Care Act, we’re expanding mental health and substance abuse benefits for more than 60 million Americans. The new health insurance plans are required to cover things like depression screenings for adults and behavioral assessments for children. And beginning next year, insurance companies will no longer be able to deny anybody coverage because of a pre-existing mental health condition.

NARRATOR: President Obama spoke there about major advances in mental health care, but they referred primarily to regulation of private insurers, not mental health care for the indigent. Phrases like Medicaid match; transinstitutionalization; and other government gobbledygook where euphemisms for reduced care and perhaps worst, a wild differential in state hospitalization rates based on how your state plays the game with some ups and downs, every president since Johnson cut more of the funding and with no funding for hospitals and a homeless population rife with mental illness, self-medication and desperate poverty, jails have become America’s largest mental health providers. The reality is that police not a doctor, not a social worker. Cops are the first responders to mentally ill people in America.

KEN BENNETT: The hospitals are full and there’s no other way to get around it unless we want to build more hospitals. It seems like we’re okay building more jails.

Ken Bennett

The BIU does a mental health patrol each weekday with officers and clinicians working together as a team patrolling the neighborhoods. They have a list of people with mental illnesses. They call them clients, and the BIU drives around and checks in on them, makes sure that they’re on their meds or keeping their appointments. Sometimes this means driving them to the clinic or to a homeless shelter. Ken says there are about 6,000 people in his community who act exactly the way the Community Mental Health Act envisioned their treatment compliant. They keep their appointments. They’re doing great.

Those aren’t Ken’s clients.

KEN BENNETT: For the small population of clients that we’re dealing with. These clients are not treatment compliant. They’re not med compliant, and they might have a history at a local clinic, but they’re no longer in services. So now what’s happening? They’re coming in contact with law enforcement.

NARRATOR: In Hurst, Euless and Bedford, H-E-B, the purpose of the BIU when it was founded three years ago, was to increase jail diversion, bringing people with minor charges who didn’t really need to be in jail to mental health services instead of jail. I think it’s worth noting how far ahead of the curve these cities have been. The BIU is an expansion of a program begun almost a decade ago as the Hurst Crisis Intervention Team model, a joint effort between MHMR, the agency, and Hurst PD to accomplish its mission. BIU officers need to know the community and to be able to step in during situations in which regular patrol officers might not be an ideal first responder.

What they aren’t looking to do is diagnose. The officers aren’t permitted to do that, but they are gathering what are known as diagnostic impressions, articulable facts and observations of a trained officer to be communicated to a mental health professional. Here’s Officer Casey Sanders, a mental health peace officer assigned to the Euless BIU.

OFFICER CASEY SANDERS: If they’re quiet and they’re very flat affect, we can probably determine they’re depressed. If we’re talking to them about the weather and they start talking about the pope and black ops, we might say, you know, their thoughts are disorganized cases.

Officer Casey Sanders

OFFICER CASEY SANDERS: We look at their mannerisms, their their state of hygiene, their living conditions, whether they’re carrying on a cohesive conversation, whether the thoughts are organized. We make all these behavioral analysis as we’re talking to them, and we form the diagnostic impression on that. And the diagnostic impression is all we need. Just a just a little impression. We’re not trying to make a clear diagnosis. We’re just kind of getting an impression on what’s going on.

NARRATOR: That’s a non-prescriptive set of non-trivial tasks and it’s intended to be. Civil Libertarians are rightly concerned that without rigorous standards, police could, for example, rouse the homeless into situations where they’re confined just for being homeless. So every weekday BIU goes out and patrols. Sometimes they’re checking up on their clients, seeing how they are. They listen to the radio for calls that might have a mental health component. Even a domestic dispute might qualify, depending on what’s coming over the radio. Sometimes they’re taking radio calls from dispatch.

OFFICER CASEY SANDERS: Specifically for them, the most common call is a suicidal person. They have expressed to someone, sometimes over social media, sometimes texting others that they’re suicidal and thinking about hurting themselves, killing themselves.

NARRATOR: And this is the part where it gets hard. We regularly hear in the media reports about how cops get it wrong and the cost of being wrong is really high. It’s often someone being injured or killed. We’re talking about a group of officers whose job it is not to confront the mentally ill on the street, but to seek them out. That’s fraught with challenges. As soon as they make a mistake, experts and parents will be saying, understandably, how upset they are that the cops got it wrong. Here’s the most constructive example I could find. Professor Megan Ryan from Southern Methodist University speaking after the death of a mentally ill young woman at another agency.

PROFESSOR MEGAN RYAN [ARCHIVAL AUDIO]: This situation could have happened differently. I think, perhaps with more thoughtful action on the part of the police officers. Maybe the death of this young woman could have been avoided.

NARRATOR: It’s hard to disagree with that statement, but let’s go one step further and ask ourselves what thoughtful means. How do you thoughtfully encounter an upset, agitated person you might not even know is mentally ill? I have a hard time understanding the difference between someone who’s mentally ill and somebody who’s very intoxicated on drugs or alcohol. I bet that many people who use phrases like de-escalation training haven’t thought the next part through. If somebody’s shouting hysterically or focusing on a dangerous task and won’t acknowledge you, the question is what’s next?

Like, literally, what’s next?

OFFICER CASEY SANDERS: Goodness. I guess the first thing is, is to be very non-threatening and to to establish that you’re there to help them. A lot of it is not not appearing that you’re trying to argue with them or find blame with them. You want to get to the point where you establish some rapport, where you can change their behavior. And that all begins with empathy.

NARRATOR: This is one of the most vivid examples of how in law enforcement we can argue about policies and oversight, about transparency and procedures. But when things happen, they are intimately human, dynamic, interpersonal encounters. I’m reminded of the Mike Tyson comment that everyone has a plan until they get punched in the mouth. Plus, there’s Casey himself. I’m trying to see how he would not seem like a cop, how he would be non-threatening.

On different days of the week, Bennett rides out with officers from Hurst or Euless or Bedford. He’s got close cropped hair and he wears Oakley Wraparounds. Bennett is former Army and he’s a clinician, but he kind of looks like a cop. Cops relate to and trust cops. So when you have a guy who looks like a cop riding with you, it can be good or it can be bad. Later, Casey told me plainly why Ken has the respect of the officers.

OFFICER CASEY SANDERS: He’s willing to get out on the street and really get dirty. He’s negotiated with armed, suicidal subjects face to face. You won’t find a lot of clinicians that do that.

BACKGROUND POLICE RADIO, CAR SOUNDS

NARRATOR: When we hit the streets about 15 minutes in, we drove by Carr Park. Bennett spots a homeless man sleeping on the bench of a picnic table. We got a homeless guy right there sleeping. It wasn’t easy to see. The guy was probably 100 yards away from the car as we drove by. But Ken saw him and then Casey called it in on the radio and gave a description of what the guy was wearing.

FIELD RECORDING

OFFICER CASEY SANDERS: 284 checking a subject.

POLICE DISPATCHER [ON RADIO] Go ahead

OFFICER CASEY SANDERS: He’s a white male, blue jeans and gray shirt. 508. Simmons.

NARRATOR: I was sitting in the back and I would have bet $1 million that there was no homeless guy.

Carr Park is where in March of 2016, a meth addict shot and killed Euless Officer David Hofer. Hofer had asked to see the man’s hands and the man shot him at point blank range.

The previous day, high on meth, Hofer’s murderer had been arrested for public intoxication and released the morning of the killing. His family blames police. It’s their fault. The killer’s father told the Fort Worth Star Telegram, ‘Why would they let him out when he was on that stuff?’

Today, we’re walking close to where that happened. I see an older man with a beard, wearing a baseball cap, lying on the bench of a picnic table. We approach him and he sits up with difficulty. He’s wheezing.

FIELD RECORDING

KEN BENNETT: We’re the mental health guys. My name is Ken. I’m the mental health coordinator for Hurst, Euless, and Bedford PD. Officer Sanders is our mental health peace officer. And so we do a lot of work with the homeless. And we just saw you over here sleeping. We want to see if there’s anything we can do for you to get you some help.

FLOYD: Man, I wish y’all could. I mean, I don’t want to be out here.

KEN BENNETT: Your ribs are broken now?

FLOYD: Yeah.

KEN BENNETT: Trying to make it. How’d you break your ribs?

FLOYD: I fell.

KEN BENNETT: Where’d you fall at? Did you fall here? In the park or …

FLOYD No, up there.

KEN BENNETT: Okay. I see you have a hospital band on.

FLOYD: Yeah, I just got out.

KEN BENNETT: What? Did you get out? Okay. Did they check your ribs out?

FLOYD: Yeah.

KEN BENNETT: What did they say?

FLOYD: They’re broke.

KEN BENNETT: Told you they’re broke. Did they do anything for them? No. Okay, let me see your hospital band. Is it a … what’s the date on that? Ten six of 2017?

NARRATOR: As Ken is looking at the hospital band, seeing when the guy was last looked at. Casey, who’s been behind the man, moves to a different angle and says, Hey, is that you, Floyd?

FIELD RECORDING

OFFICER CASEY SANDERS: Floyd?

FLOYD: Yeah.

OFFICER CASEY SANDERS: I didn’t recognize you.

NARRATOR: I think Casey is genuinely happy to see him. Then he tells us a little bit about Floyd, how Floyd has only been homeless for about ten years. But before that, he’d owned a house right there in Euless.

FIELD RECORDING

OFFICER CASEY SANDERS: Floyd has the distinction of having everything happen to him. He’s still alive. He’s been stabbed, shot, run over. He’s been around a long time. Right. So how old are you, Floyd?

FLOYD: I’ll be 65 by next birthday.

NARRATOR: And no matter what I said about how Casey looks, you’ve heard him. He’s doing exactly what he said he would do. He’s empathetic, he’s non-threatening. He’s helpful. He’s exactly who should be doing this. Casey calls the medics, and Floyd, Ken and I chat a bit. Ken looks concerned to me. Floyd is being rational and cooperative, but he’s in a lot of pain. It’s hard for him to speak, and he’s clearly in discomfort. He’s not asking for anything, but I notice that he accepted the help pretty quickly. Ken asks Floyd if he’s got any mental health diagnoses. At first, Floyd jokes about it, saying his diagnosis is that he’s throwed off.

FIELD RECORDING

OFFICER CASEY SANDERS: Floyd, do you have a mental health diagnosis.

FLOYD: Yeah, I’m throwed off.

OFFICER CASEY SANDERS: You’re throwed off?

NARRATOR: A Texas euphemism for mentally ill. But then he says he has a diagnosis of clinical depression. As we’re waiting for the medics, I notice a few more things, but basically, I was missing everything. Ken wasn’t. Casey wasn’t. In fact, what I was seeing here was exactly what Casey had described to me. Floyd’s affect was flat. He was quiet when he reported what he was feeling. He didn’t exaggerate this guy saying he’s sleeping on a bench with broken ribs and he can hardly breathe. But what he’s not doing is complaining about it. Floyd’s worried he won’t get into homeless services because he doesn’t have an ID, and he also doesn’t have the money to get his prescription for pain medication filled.

FIELD RECORDING

OFFICER CASEY SANDERS: …some resources to get you hooked up with homeless outreach, maybe go to a shelter and they can hook you up with clothing and some food.

FLOYD: I have no ID. They won’t let me go to the shelter.

OFFICER CASEY SANDERS: Well, they’ll help you get the ID, They’ll help you. Here’s what I want you to do when you get out of the hospital. I want you to call this number right here. Okay? You’ll get a hold of us. We’ll come by and pick you up. We’ll take you down to Homeless outreach. We’ll drive you down there. They’ll help you get an ID so you can get in the shelter, and they’ll help you get back on your feet. And you’re going to qualify for services since you have clinical depression.

NARRATOR: What’s interesting to me is that Hurst and Euless and Bedford are doing this thing, this totally non-standard thing, in which they’re providing a combination of social services and policing, which runs counter to the conventional wisdom about policing, where a common statement is ‘we’re cops, not social workers.’

I wouldn’t say cops are the best way to handle this, but I can’t help but notice that no one else is around to find Floyd and bring him back into the hospital. I mean, here’s a guy lying on a park bench who can’t breathe, who’s in so much pain. He’s contemplating suicide. If not the cops, then who?

It’s cheaper to do it this way. It’s cheaper to bring him directly to the county hospital and get him the help he needs than to wait for him to get in trouble or to commit a crime and then have to go sort that out. But as Ken says, we’re all fine to spend money to build new jails, but not to build new hospitals.

As if mental hospitals are a sign of creeping socialist laziness. While jails are a sign of strength in the face of threats to public safety. One of the biggest problems, in fact, faced by BIU is a result of trying to divert to mental health facilities that have no beds available. The question administrators always ask when trying to solve this problem is divert to where? Still, I didn’t have an understanding of how credible was Floyd’s outcry in the police car as we drove to the hospital behind the ambulance? I asked.

OFFICER CASEY SANDERS: But even for a guy that’s been through so much as he has, like I said, he’s literally had all those traumatic events, stabbing, shooting, run over. He’s a fighter, you know, And for him to come out and say, yeah, I’m depressed, I’m suicidal, and that carries a lot of weight.

NARRATOR: I don’t get the feeling that Casey is easily hornswoggled. The other thing is that he actually knew Floyd. He had a baseline to compare against.

KEN BENNETT: That’s the good thing about the BIU is that someone in the unit is going to have some historical information. For instance, Officer Sanders here had that historical information. So when we when we look at how to articulate this, you know, we take a guy that probably would never ask for help and he’s at that point now where he’s ready to check out, especially after everything else he’s been through, I wouldn’t doubt that he would try it. The biggest fear is that he would lay there on that park bench. He hasn’t eaten in a couple of days and he may end up just passing away.

NARRATOR: We get Floyd to the John Peter Smith Hospital, where he was admitted and checked out by a doctor. I knew one of the E.R. nurses…

FIELD RECORDING

E.R. NURSE: What are you doing here? Go this way.

NARRATOR: She gave me a hug. And then when we got into the room, she asked Floyd a lot of the same questions that Ken and Casey had asked.

FIELD RECORDING

E.R. NURSE: They told me you had thought to hurt yourself.

FLOYD: Yeah.

E.R. NURSE: Tell me about that.

FLOYD: Oh, pain is making me depressed.

E.R. NURSE: The pain is making you depressed. Do you have a plan to hurt yourself?

FLOYD: No, not really.

E.R. NURSE: Not really?

OFFICER CASEY SANDERS: You told us you were going to hang yourself, Floyd

FLOYD: I’d like to.

E.R. NURSE: Have you made any attempts today?

FLOYD: No.

E.R. NURSE: Have you taken any drugs or alcohol? Any prescription drugs …

NARRATOR: And then we hit the road again. From BIU’s perspective, this was an easy case. They seek to help people before there’s a crisis. It doesn’t always go this easily. Sometimes the people are angry. Sometimes they fight. Urinate on themselves or on you. Run. Sometimes they’re committing serious crimes and they have to be locked up. This all comes into specific focus this year with the passing in Texas of the Sandra Bland Act, named for the young woman who was found dead in a Texas jail just days after a white state trooper arrested her in a confrontational encounter. Here’s what most people in America remember about Sandra Bland.

AUDIO FROM BODY CAMERA FOOTAGE

TEXAS STATE TROOPER BRIAN ENCINIA: [YELLING]: Get out of the car … I will light you up! Get out!

SANDRA BLAND: Wow.

TEXAS STATE TROOPER BRIAN ENCINIA: Now!

SANDRA BLAND: Wow.

TEXAS STATE TROOPER BRIAN ENCINIA: Get out of the car!

SANDRA BLAND BRIAN ENCINIA: For failure to signal. You’re doing all of this for failure to signal.

TEXAS STATE TROOPER BRIAN ENCINIA: Get over there!

NARRATOR: The arrest was wrong. The trooper was an ass. And then he lied. He was charged with perjury and fired. But Sandra Bland didn’t die when she was arrested. She said during jail intake that she had recently attempted suicide instead of being brought for mental health observation. She was confined in the Waller County jail in conditions that were wholly inappropriate for someone with mental illness. She committed suicide after three days in that cell.

The Sandra Bland Act shifts responsibility for caring for and helping the mentally ill back to Texas’s mental health care system. It’s a major piece of legislation that can be a game changer. It says that the place we were tucking away the mentally ill for so long in a way that made them so hard to count is less of an option now.

Whether Texas’s mental health care system has the capacity to handle a major influx of new patients is a troubling, unanswered question. Once it adapts, however, Texas will lock up fewer people for whom jail is a wholly inappropriate measure.

The BIU predates Sandra Bland by three years. And while very few people have a BIU, it’s not as if other agencies are doing nothing. Last week, Tarrant County Sheriff Bill Waybourn sent out an email to every police chief in Tarrant County saying that if they had someone in their jail with a mental health issue, they could be sent to Tarrant County Jail, in which there’s a forensic unit with a full time psychiatrist.

SHERIFF BILL WAYBOURN: We’ll take them. We will take them so that we can get them straight into services so they don’t decompensate.

NARRATOR: Because finding beds for an inmate with a mental health issue is very challenging. Every jail has the Divert to Where question.

SHERIFF BILL WAYBOURN: We’ve got 41 municipalities and over 51 agencies that may be dealing with these people, from hospitals to universities to railroad cops.

NARRATOR: Most of the 51 agencies in the county don’t have the officers to spend, sometimes up to an hour getting someone signed in to Tower ten, a room at filled with recliners and people milling around, waiting for disposition. It can take a lot longer if the client needs medical attention first.

In Tower ten, where the client will sometimes wait for a day or more to get one of their 96 beds, only to be sent out to the lobby where they’ll wait 4 to 8 more hours to get back in and then start waiting again. Time is important. Sheriff Waybourn used the word decompensate, a term of art that describes someone who’s starting to lose their ability to maintain normal psychological demeanor and revert to anxiety or delusions or even plain depression.

Tarrant County, like Hurst, Euless and Bedford has moved to get all their officers certified as Texas mental health peace officers. If you’re going to have a mental health unit in the jail, it should be a good one.

Sheriff Bill Waybourn (L) and Corporal Nova

SHERIFF BILL WAYBOURN: We’re trying to employ other things in our jail, including Corporal Nova.

NARRATOR: Can you, can you describe…

SHERIFF BILL WAYBOURN: Yeah. Corporal Nova is our is our service dog. And she just came back from the jail. She’s in the briefing with our people. She’s been patrolling pods today. She’s just trying to lower and de-escalate things in the jail. She’s a comfort dog for the jail, and victims and everything else.

NARRATOR: I’ve known Waybourn for ten years. I’ve never thought of him as a “service dog” kind of guy. He’s more of a numbers guy. I asked him about the cost of the training and he dismissed it.

SHERIFF BILL WAYBOURN: We got to do ongoing training anyway, and it’s just part of the practice of law enforcement today.

NARRATOR: Divert to Where…

HALEY STEWART: A lot of times you can’t divert someone to a long term facility because they don’t have an ID or their their Social Security card isn’t right or they have a different alias.

NARRATOR: That’s my friend Haley Stewart. We went to the police academy together. She worked at a county hospital as a mental health peace officer, and now she’s pre-law at Texas Wesleyan, interning for the county mental health court judge. When she passes the bar, she wants to practice mental health law.

Haley Stewart

NARRATOR: Something you should know about Haley. She takes this very personally. In the academy, they asked us all a question: Why do you want to be a cop? Lots of us said goofy stuff about driving fast and carrying guns. Haley said, Because I’ll get to see people on the worst day of their lives and I’ll have a chance to make a difference. She still believes that. So do Ken and Casey and all the officers at. Sometimes it’s frustrating. Sometimes it’s heartbreaking.

HALEY STEWART: It’s surreal to stand two feet from someone and have them tell you how they’ve plotted to kill themselves. And some of them were successful.

NARRATOR: After you talked to them?

HALEY STEWART: Yep. Some were homicidal, and after the hospital kicked him out… They carried out the homicide.

NARRATOR: Divert to where …

KEN BENNETT: It’s not only a crisis here locally, it’s a state crisis. And I think it’s a crisis around America. And we’ve got to figure out how to solve it. What’s going to be the best way to handle these people to where we can get them the appropriate treatment they need, get them stabilized and get them to where they’re no longer a danger to self and others.

NARRATOR: Texas cops get a hugely unfair reputation in the northeast and the Northwest. The guys I’ve introduced you to here are, in my experience, great examples of why I think that. And some of this is our fault. Texas legislators have fairly often in recent memory, taken a ride one stop too far on the crazy train. People poke fun of Texas. They think we’re the state with the drive up window for executions packed with gun nuts and yahoos.

But look what Texas has done. Every officer in the state is mandated to get mental health response training and update it every two years. The Sandra Bland Act requires more in terms of mental health of Texas jailers and sheriffs than anywhere. Texas is the future of mental health policing in America.

Casey’s in.

OFFICER CASEY SANDERS: This job suits all of my talents and abilities. Some people have just a natural ability to do it. I happen to have that natural ability, I suppose.

NARRATOR: In ten years, I bet we see a lot more agencies across the country running programs like Ken’s BIU and Sheriff Waybourn’s comfort dog and intelligence program. Even if it doesn’t always work out.

Two days after we were in the E.R., I heard that the hospital thought Floyd was drug seeking. After a few hours, apparently he forgot his main complaint was suicidal ideation. But remember, that wasn’t his chief complaint. His chief complaint was that he couldn’t breathe.

FIELD RECORDING

OFFICER CASEY SANDERS: Wouldn’t you agree?

FLOYD: I can’t breathe.

OFFICER CASEY SANDERS: You can’t breathe? Okay? You want you want the paramedics to come out and check you out?

FLOYD: Yeah, I guess.

NARRATOR: Remember I said earlier, he didn’t actually ask for anything. But in an overcrowded system, after seeing EMTs and admitting nurse an E.R. doc, a psych nurse, a psych doc, the system is trying to weed out and triage. Of course, they’re suspicious of people. I don’t blame any of those people. And also, by the time all those people got to see him, he had been fed for the first time in three days. He’s got some morphine on board, so his pain is more bearable. Maybe he wasn’t as suicidal as as he was when we found him in the park. Or maybe he suckered us. How do you tell the difference?

HALEY STEWART: That’s a great question. How do you tell the difference between someone who’s truly suicidal if they tell you they’re suicidal and someone who isn’t?

NARRATOR: There’s just nothing easy about this job. And that starts with how few people understand it. They demand it’s done, but very few people seem concerned with the details until something bad happens. Then they want answers. But it’s hard to understand the answers you get when you truly don’t understand the size of the problem, the context in which people do this work. So often when you get the real answer, it doesn’t make sense.

I think about the willpower it took for Ken to envision and create a job and a strategy no one asked him to create, to convince the chiefs of police, the city council, the mayors, the lawyers of three cities to try something so new, you can’t even agree on how to measure success.

And I think about the risks that all those officials took in moving forward at all. There was no political penalty for not doing this, and they did it.

When I think about America’s political turmoil, that public servants like these still exist gives me great hope.

KEN BENNETT: This is a this can be a very emotional job and that you’re dealing people with people at their very, very worst. And you’re going to see some very, very bad things. And every call you deal with is going to be someone mentally unstable. And sometimes you’re going to get there after they’ve already committed the act. We realize we can’t save everyone, but if we do our jobs and we’re proactive, we’ll probably save more than we would have if we did nothing at all if we just took a reactive approach.