Yet Another Year-Of-The-Linux-Desktop Piece

This article originally appeared in the International Herald Tribune/NY Times

A Cannes-based private investigator, Alain Stevens, recently switched computer operating systems from Windows to Linux. “It’s a security issue,” Stevens said. “Viruses which target Windows could send confidential documents from my machines to random people — and that could send me to prison.”

Citing cost savings, open standards and enhanced security, the German government in June reached a Linux deal with International Business Machines Corp. and SuSE Linux AG of Germany for its local, state and federal computer infrastructure.

And as the City Council in Nottingham, England, plans a new software application for 10,000 employee workstations, it is seriously asking the question, “Are we going to run this on Windows or open-source, like Linux?”

Throughout Europe, companies and governments large and small have recently been asking the same thing. Information technology departments are looking at what they have and rethinking what they want.

The resulting groundswell could soon make the Linux-based desktop more prevalent in Europe than anyone could have predicted even a year ago. Dan Kusnetzky, an analyst for International Data Corp., said Linux had a 3.9 percent share of desktops worldwide, outpacing Macintosh’s 3.1 percent.

Richard Heggs, Nottingham’s systems analyst, described the process this way: “We’re looking at Linux as a possible replacement for Windows as council desktop standard. It’s looking favorable. Senior management is saying, ‘We like this, but can it do what people say it can?"’

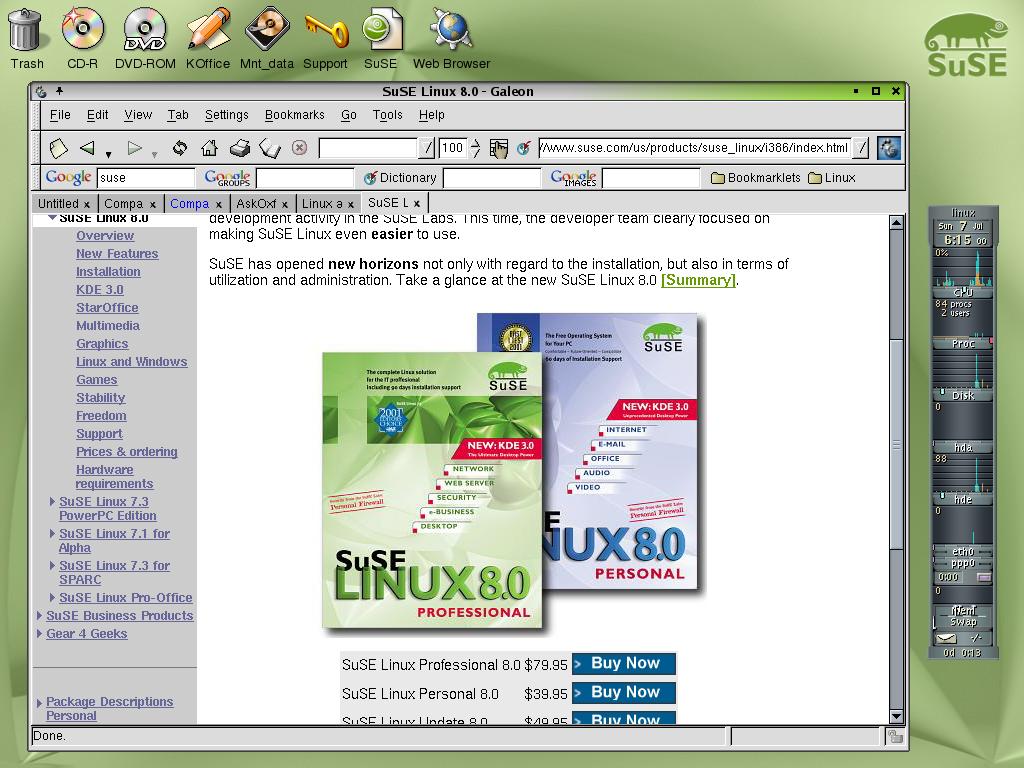

The stimulus to find out has been manifold. A new generation of user-friendly Linux products spearheaded by SuSE and MandrakeSoft SA of France — both of which are small, as yet unprofitable companies — has eased migration.

Legislative incentives have put open-source on corporate tongue-tips. Countries including Britain, Germany, France, Italy, Norway and Malta have introduced a flurry of initiatives to give open-source software access to a level playing field — and mandate the use of open standards for official communications.

And Microsoft Corp.’s unpopular license-fee revamping has contributed to a general re-evaluation of IT purchasing criteria: Some tech managers say their feasibility studies of Linux migration may be justified by reasoning that, at a minimum, the results are ammunition for negotiations with Microsoft.

Companies still look for big names — like Microsoft’s — behind any new software they might buy. Now, other big names in computing are putting money behind Linux products.

Sun Microsystems Inc., which recently announced an Intel-based server pre-loaded with Sun Linux 5.0, contends that the concept of having “one folk to choke” support for an open-source product lends credibility to open-source. “The key value Sun’s bringing to Linux isn’t really ‘on the tin,"’ said Simon Tindall, volume products business manager for Sun in London, “but that we will support it directly as a vendor.”

This type of Linux support means that corporate IT departments and purchasing managers, ever wary of getting stuck with something forever, can now say, “Well, Sun’s providing support for it.” For example, BEA Systems Inc., IBM, Oracle Corp., SAP AG and Veritas Software Corp. have all ported their applications to run on Linux systems.

All this effort may raise costs (Linux costs typically have nowhere to go but up), but that may not be a deterring factor.

Consider StarOffice, Sun Microsystems' open-source challenge to Microsoft Office, its word-processing business software suite. Until recently, it cost nothing. Since release of version 6.0, Sun has begun charging up to $79 per license

The price seems to make businesses trust it more, some analysts say — it is a real product with a viable revenue model, which is a lot easier to explain to your boss than a product supported only by eleemosynary efforts by some vaguely hippie-sounding “open-source community.”

James Jarvie, IT manager of the Central Scotland Police, said the £245,000 ($380,000) they saved on licensing fees with StarOffice paid for more police on the streets. Councils in Aberdeen and Penwrith have embraced it, and the British Office of Government Finance has now endorsed it, along with Office and Lotus’s SmartSuite.

“Unless Microsoft makes significant concessions in its new Office licensing policies,” Gartner Inc. said in a research report, “StarOffice will gain at least 10 percent market share at the expense of Microsoft Office by year-end 2004.”

To stand a chance, an operating system must provide applications that allow users to seamlessly edit and exchange documents with others (which often means “with Microsoft Office users”).

StarOffice is about 95 percent compatible with Microsoft Office (macros don’t translate, but for everyday files it is more than adequate). It runs on Windows, Linux and Solaris, and since the user interface looks identical on Windows and Linux desktops, a major changeover for users would be easier.

“Running StarOffice on Windows,” said MandrakeSoft’s chief executive, Jacques Le Marois, “is almost always a strategic migration choice.”

Martijn Dekkers, chief enterprise architect for the prime minister’s office in Malta, agrees.

“The key barrier,” Dekkers said, “is office suites and collaborative tools like e-mail and Web browsers. Interface similarities ease transitions between different operating systems.”

Ten months ago, Malta began investigating the culture and benefits of open-source. Where big software vendors claim that open-source is unreliable, unsupported and untrustworthy, open-sourcers assert that its products are the solutions to the world’s ills. The truth is perhaps neither, but on the issue of support, Dekkers found open-source viable.

“We have found,” Dekkers said, “that one of the major issues put forward — no support and no accountability — is false.

“Small and large open-source vendors offer support which is equal to or better than support from main commercial developers.”

While large organizations typically take a long time to weigh such issues, some smaller businesses in Europe are switching to SuSE and MandrakeSoft for their desktops.

Last year, SuSE implemented its SmartClient architecture on Linux for Debeka-Gruppe, a German insurance and financial services group.

More than 3,000 workstations in 230 German locations are administered from its corporate headquarters in Koblenz.

Where governments deal with issues of open-source culture and monopoly-busting, small companies indicate three main reasons for taking the plunge: reliability, security and cost.

“I switched,” said Mervyn Cottenden, an Essex accountant who runs two MandrakeSoft Linux machines, “because Windows is unreliable. I can’t afford to lose a client’s work because a machine goes down in the middle of a job.”